The final numbers are in. $24 million is budgeted for the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway in 2019. What does this mean for boaters? Bottom line is that some of those problem areas where bumping along, looking for the deep spots or stuck in the mud waiting for high tide will be cleaned out in the months ahead. Dredging contracts are being signed and plans are in the works.

Between the President’s Budget and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ (USACE) Work Plan, the states of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida have $24 million to spend on keeping their waterways operational and dredged. This is in addition to over $40 million in Fiscal Year 2018. (See list of projects at end of article.) While the latest round of funding is the highest amount received for the waterways in many years, there are challenges.

Leaders, experts and stakeholders from across the U.S. convened during the recent annual meeting of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway Association (AIWA) in Charleston, SC to discuss the issues associated with managing the processes, regulations and future of what is often referred to as America’s Marine Transportation System. Speakers covered the complexities of security, policy and regulations, and the intricacies of what to do with material dredged from those dreaded shallow spots. It’s not an easy fix.

You can remove the sand and muck, but it must go somewhere. And there are fewer and fewer locations where the dredge materials can be placed feasibly and economically.

Executive Director of the AIWA, Brad Pickel, says, “Dredge material management is as big, or bigger, than getting money. The issue is helping us find ways to dispose of the materials. Real estate is the principal problem for dredge material. For example, the value of land along the ICW has increased so much that simply moving it alongside the waterway is seldom an option. Further, states and localities often want the material to be confined for any number of reasons.”

During the 2018 AIWA conference, experts presented solutions for managing dredge material including Thin Level Placement (TLP), Nearshore Placement, beach replenishment and Engineering with Nature. Pickel adds, “Dredge material should not be considered a liability. It should be seen as an asset in the natural system. The AIWA’s mission includes assisting in finding ways to do that and bringing decision-makers to the table.”

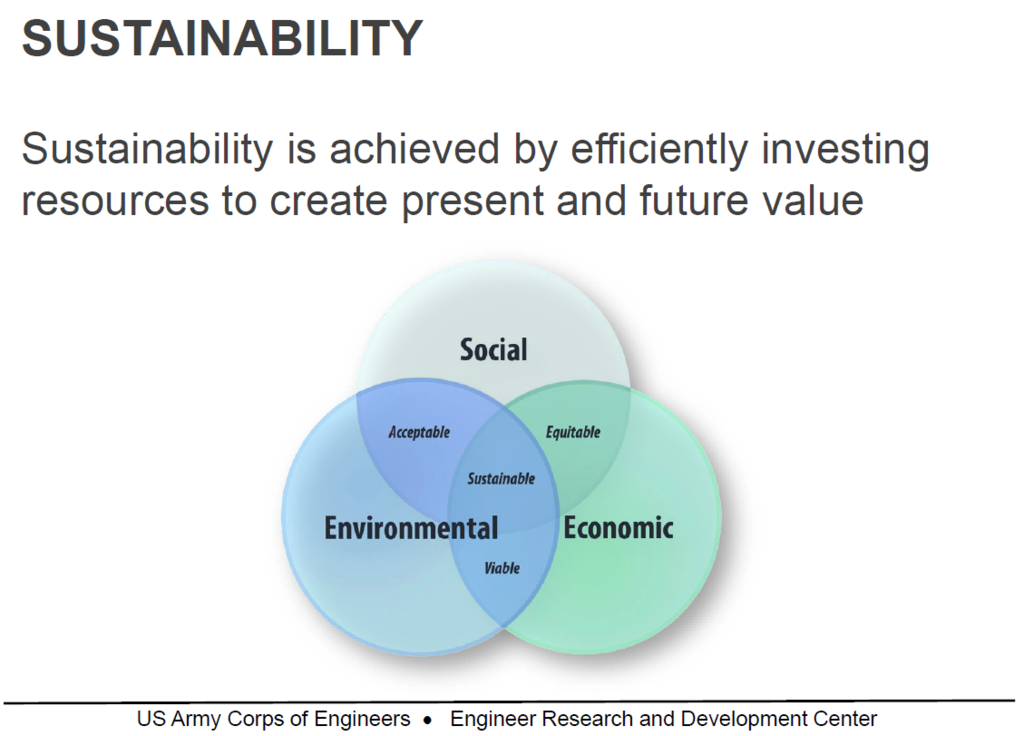

One of the more compelling sessions during the conference was presented by Todd S. Bridges, Ph.D. from USACE and Brian P. Bledsoe, Ph.D., P.E. from the University of Georgia. Engineering with Nature: Toward Sustainable Systems outlined the ICW as “an organized system” comprising changing conditions, low use equals low funding, limited placement/disposal areas and capacity, and additional descriptions including understanding and managing system performance and value over the long-term. Sustainability was presented in terms of Social, Environmental and Economic components.

Measuring the value of our waterways has traditionally been focused on “commercial use.” Specifically, how many tugboats and barges use the waterways and what amount of commerce do those vessels and their cargoes generate? But there’s a new paradigm that proponents of our waterways are formulating to encourage policy makers and funding agencies to recognize that health and happiness is not measured solely by trade. For those of us who spend many days, and even weeks, on the Intracoastal Waterway this is evident when gliding along at 6 knots in seemingly isolated stretches of flourishing marshes and shorelines. The peace and quiet and freshness of the habitats evoke contentment. Dr. Bledsoe referenced a study from the Center for Occupational and Environmental Health at UCLA that Urban River Parkways are “an essential tool for public health.” Every $1 spent on recreational trails results in $3 to $10 of direct medical benefit. So, it appears that social capital, happiness and health are valid economic yardsticks when calculating the value of open and natural spaces like the ICW.

In answer to the question of whether Federal funding sources recognize recreation as a valid reason for providing funding for maintenance of the ICW, Pickel says, “I think it is accurate that recreation is not considered for budgeting, but other metrics are used for budgeting in addition to tonnage. ‘Commercial use’ is probably an accurate way to categorize the funding, but not the old interpretation of commercial tonnage or commercial ton-miles. This broader category can include value of the waterway to smaller towns and cities that rely on it, such as working waterfronts. I think funding is also increasing in places like Georgia because of the interconnection of the entire system from the northeast through Florida. It is being treated like a Marine Highway that is only as strong as its weakest link.” Evident of the importance of the ICW as a marine highway is the addition of 95 in its name by some who recognize that ships and barges employing the waterway relieve cargo truck traffic on the north-south corridor.

As this year progresses, recreational and commercial vessels will see improvements in many of the problem areas of the AICW, as well as other infrastructure improvements. Since most of you reading this article are subscribers to Waterway Guide News and Nav Alerts, you are most likely recreational boaters, or offer facilities and services to boaters. We encourage you to stay current on matters affecting America’s waterways and use every opportunity to alert your local, state and national representatives of the issues surrounding dredging, funding and infrastructure. And we encourage you to join us in supporting the AIWA with your membership. The cost is only $25 for an individual boater and small businesses and marinas start at $250.

Here is the direct link. “The mission of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway Association (AIWA) is to encourage the continuation and further development of waterborne commerce and recreation in the Intracoastal Waterways of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida through the promotion of adequate dredging, safe navigation and maintenance; to work to ensure that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintains the waterway at its authorized width and depth as authorized by Congress; and to educate the nation and the region about the historical and economic value of the waterway to its citizens.”

A list of dredge projects and proposed projects presented by USACE for 2018-2019 subject to available funding.

Great Bridge Locks Pump Replacement

North Landing Bridge Electrical Upgrades

Shalotte River Crossing

Snows Cut

Lockwoods Folly Inlet Crossing

Brown Inlet Crossing

Carolina Beach Inlet Crossing

New River Inlet Crossing

Channels to Jacksonville

Shinn Creek Crossing

Mason Creek Crossing

Breach Inlet

Dewees Island

Capers Island

Graham Creek

Awendaw Creek

Matthews Cut

Jeremy Creek

South Santee River

Four Mile Creek

North Santee River

Little Crow Island

Minim Creek

South Island Ferry

Charleston to Port Royal

Georgetown to Charleston

Jekyll Creek

Hells Gate

Cumberland Dividings

Buttermilk Sound

Fields Cut

Wright River

Elba Cut

Little Mud River

Walls Cut

Creighton Narrows

Rockendundy River

Altamaha Sound

Sawpit

St. Augustine

Matanzas

Broward Reach 1

Volusia

Ponce Inlet

Jupiter

Crossroads

Note: The Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway is abbreviated as AIWW by most agencies. It’s known as the AICW by the U.S. Coast Guard in some of its postings. Most boaters call it the ICW. By the time you reach central Florida, it’s known as the IWW. Then there’s the Gulf IWW and the NJ ICW. You get the drift.

However you might refer to them, they are the same protected stretches of waterways that keep us out of the big water and close to marinas, towns and anchorages.