As temperatures yo-yo from near freezing, to T-shirt weather, boaters taking a day trip, or participating in a winter sailing series, may find themselves underdressed and in distress.

On Sunday, I decided to spend the day out on the committee boat for a local dinghy sailing “Frostbite” series. I've run the committee boat for several years. This year it was someone else's turn and I decided to volunteer to shoot some video. The committee boat is a 16-foot-long, wide-open, Panga outboard skiff.

Despite the fact that it had been in the mid-60s that week, it was down to 40-degrees and gusting from 10-15 mph.

Therefore, I dressed as if I were going to summit Everest. I followed the first rule of survival attire taught to me by my husband, Robert Suhay, Guinness World Record Laser dinghy distance record holder twice over. He taught me that “cotton kills.”

The phrase is a reminder not to wear cotton between November 15th and April 15th for any kind of winter activity, especially sailing. That’s because of the way cotton fabric handles moisture against your body.

Author Cody Lundin puts it this way in survival book “When All Hell Breaks Loose:” “Cotton is hydrophilic, meaning it transfers sweat from your skin to the material itself, thus it’s horrible at “wicking” wetness away from skin.”

“In fact, cotton loves moisture and will become damp simply when exposed to humid air. Once wet, it feels cold, looses 90 percent of its insulating properties, is a drag to dry out, and wicks heat from your body 25-times faster than when it’s dry,” he writes. “Because of this, wearing cotton clothing in the wintertime is a death wish.”

Before I even got out there I followed the USCG checklist of “Preventative Measures for Cold Stress:”

Drink moderate amounts of water frequently.

Avoid alcohol, certain medications and smoking to mitigate risk.

Wear appropriate clothing.

Cotton looses insulation when wet

Wool retains insulation when wet

Wear layers. Outer layer to deflect wind,

Middle layer (down, wool) to absorb sweat and provide insulation even when wet,

Inner layer (cotton, synthetic weave) allow insulation/ventilation

Wear cover/hat (60% of heat is lost though head)

Wear insulated boots and full fingered gloves

Loose clothing allows better ventilation

I wore layers of synthetic materials and wool, something called a “blanket scarf,” thermal skullcap, fleece-lined gloves and one of those ugly brown Thinsulate work jackets that totally block the wind from your skin.

My mistake was wearing sneakers. I was thinking about mobility and traction, rather than warmth and waterproof. One splash and my toes went stone cold. By the end of the three-hour tour, they were completely numb.

By the time I got ashore I had “frost nip” which meant that after a shower and soaking my feet, the toes were bright pink, pinkie toes blistered and hurting.

Yet I wasn’t the in serious trouble at the end of the day. It a teenage novice who sailed, and capsized, in a thin wetsuit, booties and life jacket. He didn’t have gloves, hood or hat.

Rather than agreeing to be taken to land to get warm and dry, the young sailor opted for being dropped on the committee boat to watch and learn.

What we all learned is how fast someone becomes hypothermic in that situation as he began to shake uncontrollably, lose motor function and take on a 500-yard stare without responding to questions.

Another reason layers are excellent is that they allow a warm person – like me- to peel most of them off in order to pile them on to a freezing person. Once ashore he got into a hot shower and bundled into a warming room in time to have no permanent damage. It was still too close for comfort.

A few days later, I called Nate Littlejohn, Petty Officer Second Class with the Fifth Coast Guard District in Portsmouth, VA to find out how boaters in his district are faring in the cold.

“I stood duty over the weekend and have a couple of different instances over the weekend duck hunters ran out of gas. Got beached and stranded out there,” Littlejohn explains. “Another boat coming south on Chesapeake Bay grounded with engine trouble. In both cases, the cold weather definitely played a role in their distress. They were cold and weren’t prepared to spend the night out there in that weather.”

What boaters are lease prepared for, he adds is somebody going into the water.

“Folks are not prepared to fall into the water,” Littlejohn says. “What ends up happening to folks who don’t have a life jacket, or a way to locate them, the time is only a few minutes before it’s too late. All the blood goes to your core. So, in less than a minute you lose the ability to swim"

"Once you do end up in the water, how on earth are we gonna find you?”

Littlejohn says that having a personal EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon) or “P-EPIRB” of PLB (personal locator beacon) that is properly registered, is essential to even a brief day trip.

“The second somebody’s overboard let the Coast Guard know,” he advises. “If you get them on board and they’re fine, then call back and tell us to stand down.”

The following is a guide provided by the USCG on “Cold Stress:”

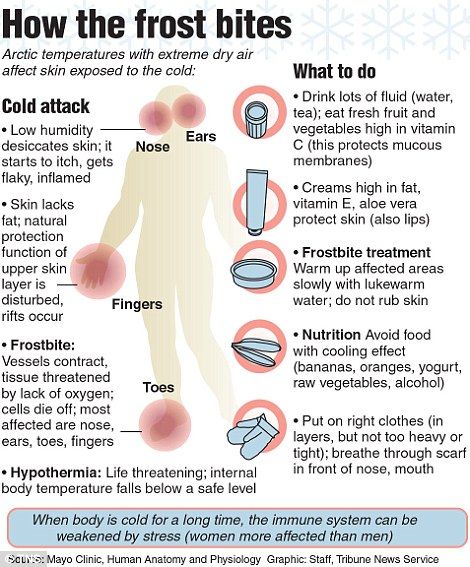

Frost nip, frost bite, and hypothermia are medical conditions associated with cold stress.

Frost nip is the first stage of frost bite when only the surface skin is frozen. Frost nip begins with itching pain. The skin then blanches and eventually the area becomes numb. Treat by moving victim to a warmer area and follow the treatment recommendations for frostbite.

Frost bite is damage to tissues from freezing due to formation of ice crystals within cells, rupturing the cells, and leading to cell death. Frost bite occurs when temperatures are below freezing. Symptoms include a burning sensation at first, whitened areas of skin, blistering, and the affected part may be cold, numb, and tingling. Treat by covering the frozen part, providing extra clothing and blankets, placing the affected part in warm water or covering with warm packs. Discontinue warming when part becomes flushed and swollen. Do not place pressure dressings on the affected area, or rub body part. Give sweet, warm fluids. Do not use heating device on part. Obtain medical assistance immediately.

Hypothermia is a reduction in core body temperature that occurs when exposure to cold causes a person’s body to lose heat faster than it can be replaced. Symptoms include pain in extremities, uncontrollable shivering, reduced core temperature, cool skin, rigid muscles, slower heart rate, weakened pulse, low blood pressure, slow irregular breathing, slurred speech, drowsiness, incoherence, lack of coordination, diminished dexterity, and diminished judgment. Treat by moving victim from the cold source. Remove wet clothing and get into dry clothing. Wrap victim with a blanket. Pack neck, groin and armpits with warm packs or warm towels. Give sweet, warm drinks. Keep the victim awake. And transport them to a medical facility immediately.

Signs and symptoms of Hypothermia:

Mild hypothermia (98-90° F): Shivering, lack of coordination, stumbling, fumbling hands, slurred speech, memory loss, pale, cold skin.

Moderate hypothermia (90-86° F): Shivering stops, unable to walk or stand, confused and irrational.

Severe hypothermia (86-78° F): Severe muscle stiffness, very sleepy or unconscious, ice cold skin. Death is eminent.