The rapidity with which a shipboard fire can spread is alarming to say the least. Some studies suggest that fires double in size every 60 seconds, particularly in the presence of highly flammable materials. Therefore, the best defense against such an occurrence is prevention. Avoiding the most likely causes of fires makes good sense. Non-ABYC compliant shore power and DC electrical systems, galley/stove mishaps and engine exhaust system malfunctions or design flaws top the list for causing fires.

While most fires are avoidable, some aren't. A flare-up on a galley stove, an internal battery short circuit, or a dock power fault, for instance, can all lead to onboard fires that simply could not be prevented. In every case, avoidable or otherwise, a rapid response is essential using the most effective tools possible–that is portable (and fixed in the case of engine rooms and engineering spaces) fire extinguishers in sufficient size and quantity.

Classifications & Details

Portable fire extinguishers classifications can be confusing, but they are typically classed using two possible categories. USCG marine fire extinguisher classifications include BI and BII for the extinguishers themselves. The suffix I and II refers to the size and is dependent upon the type of agent. Type BI, for example, holds two pounds of dry chemical agent and five pounds of CO2. The dry agent may be ammonium phosphate or sodium bicarbonate. Ammonium phosphate, usually in a yellow powder form, is often referred to as Tri-Class or ABC and is corrosive and harmful to electronics and other gear. The white powder sodium bicarbonate is not corrosive but is less than ideal for contact with sensitive electronics and running engines. UL/ANSI ratings are simply indicative of the class of fire that the extinguisher is designed to fight: A (wood, cloth, paper and fiberglass/plastics); B (fuel, oil, thinners, paints, etc); or C (for energized electrical equipment). Once de-energized, a class C fire typically becomes a class A fire.

Any fire extinguisher you purchase for your vessel should carry a CG approval and rating, and my preference is for units that rely on a metallic (as opposed to plastic) valve head. Metallic head extinguishers can be tested and refilled, while plastic head extinguishers are essentially disposable, the vast majority of which end up in landfills never having been used. Plastic head extinguishers are also prone to leaking pressure over time. When this happens you have no option but to discard them and purchase a replacement.

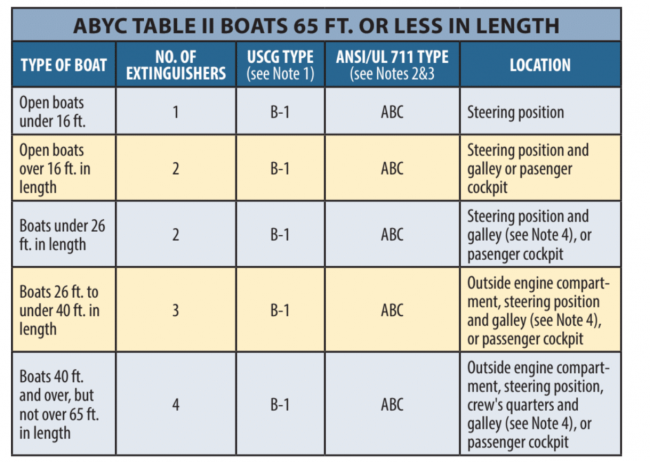

The requirements established by the USCG and ABYC for portable fire extinguishers used aboard recreational vessels should be considered nothing more than the minimum. Of the two, ABYC's requirements are more stringent, calling for four portable extinguishers for vessels between 40 and 65 feet. The CG regulations are a bit more complex, as they make allowances for fixed fire fighting systems. (ABYC guidelines make no such distinction.) If no fixed system is installed, CG regulations call for three class BI or one BII and one BI for the same size vessel. If a CG-approved fixed system is installed, these vessels may have two BI or one BII extinguisher. That's right….It's possible for a 40- to 65-foot vessel with a fixed engine room system to meet USCG requirements with a single portable fire extinguisher.

ABYC guidelines also make it clear that a portable fire extinguisher should be installed near the galley, which makes sense. It should be installed opposite rather than adjacent to or over the stove. Additionally, the guideline go on to say that a user should not have to travel more than half the length of the vessel to reach a portable extinguisher, or 33 feet, whichever is less. Imagine how long it would take you to cover 33 feet; this is a veritable eternity when a fire is raging. Considering the expense, I'd prefer to see a portable extinguisher in every cabin and compartment, requiring you to take no more than three steps to access it, as well as one outside the engine room access hatch or door. With this approach, you can never be trapped in a space without some means of fighting a fire to make your escape.

For the "Other" Types of Fire

Up to this point I've discussed a worst-case scenario, a fire that rages in your galley or engine room or one that prevents your egress from a compartment. There's no option; those fires must be extinguished at all costs. While all fires are cause for alarm, there are other types of fires that are relatively easy to extinguish and, provided they are extinguished quickly, cause little initial damage. I was aboard a vessel as it was moored dockside a few years ago. The owner decided to flush the potable water tanks using the boat's electric water pump. At some point the pump or its associated wiring overheated, which caused the wire's insulation to ignite. A portable dry chemical extinguisher was aboard and the owner used it to good effect, and the fire was extinguished quickly. However, the pump was located in the engine compartment and the engine was running. The engine ingested the dry chemical, which (I suspect) caused the valves to stick open, allowing them to be struck by the pistons, causing thousands of dollars of engine damage.

In another onboard fire scenario, the aftermath of which I dealt with, an inverter fire was extinguished using a dry chemical agent. The fire was the result of an un-fused conductor that overheated, igniting its own or adjacent insulation. The dry chemical extinguished the fire; however, in his exuberance to douse the flames, the technician on board when this occurred also dusted the inverter itself just for good measure, damaging it beyond repair.

Clean agent fire extinguishers such as the fixed units that are routinely installed in engine rooms are well suited for extinguishing such minor electrical fires. Portable units are designed for use on Class C fires (an energized electrical fire) specifically because they are clean, leave no residue or powder and their agent is non-conductive and non-corrosive. (I prefer the FM-200 series of portable units, however, there are others.) Had a clean agent portable fire extinguisher been available in either of the aforementioned cases it could have been used, effectively reducing collateral damage. It is for this reason that fixed engine room fire extinguishing systems rely on such clean agents to extinguish flames, while minimizing collateral damage to engine room equipment.

Depending on the size of the vessel, keeping one or two portable clean-agent extinguishers aboard, near the electrical panel or dashboard, and just outside the engine room access simply makes good sense.

ABYC TABLE II (BOATS 65 FT. OR LESS IN LENGTH)

- If a discharge port is installed (A-4.53.1.1), a USCG type 5-B portable fire extinguisher may not be adequate.

- Extinguishers intended for engine compartment protection in accordance with A-4.5.2.2 or A-4.6.4 are not required to have a Class A rating.

- Boats under 26 ft. in length without enclosed accommodation spaces or enclosed galleys may be equipped with a bucket with attached lanyard and a Class "BC" rated extinguisher in lieu of Class "ABC" rated portable fire extinguishers.

- On boats having galley stoves, one of the required extinguishers shall be readily accessible thereto.

"We're on fire!"

These are words that no mariner wishes to hear, yet it's a phrase for which all prudent mariners need to be prepared. A couple of years ago I received a call from clients explaining that they'd had just such an experience. What transpired, and the manner in which they dealt with it, reinforced the importance of ensuring that every vessel has the ideal firefighting tools.

In this case, the vessel was maneuvering in a harbor setting when the fire occurred in the engine room. For the purposes of this discussion, the cause of the fire, which occurred in an engine wiring harness, is less important than what occurred afterward. While idling slowly, the crew in the pilothouse noted the unmistakable odor of an electrical fire. They quickly scanned their instruments as well as the engine room video monitor; the latter was filled with a thick pall of white smoke. With a portable dry chemical fire extinguisher taken from the pilothouse, one of them proceeded to the engine room. Looking through the access door's window, he sized up the situation, took a deep breath, leapt in, loosed the contents of the extinguisher onto the fire and then raced back out. His efforts were successful; the fire was quickly extinguished.

Several who have watched the video have asked why the crew simply didn't discharge the engine room's gaseous, fixed firefighting system. While that is one course of action, and a safe one, doing so represents a significant investment of sorts, in that re-charging it is costly. While expense is of no consequence when it comes to firefighting for small, isolated electrical fires, as this one was, consideration should initially be given to a localized approach toward extinguishing the flames. Additionally, once the fixed system is discharged, the engine room is thereafter unprotected, until it's recharged, which, if cruising in a remote area, could be some time.

Steve D'Antonio is a marine systems consultant offering services to boat buyers, owners and the marine industry, as well as an author and photographer. He is an ABYC-Certified Master Technician. Read more from Steve at www.stevedmarine.com.