A few years ago, I received an email from a reader, to which a photo was attached. The subject of the email was “Shouldn’t the circuit breaker have prevented this?” The photo depicted a boat and a marina owner’s worst nightmare: a seriously burned (“charred” might be a more apt description) shore power cord end and boat-side inlet.

The short answer to the question was “No, not necessarily.” With a few exceptions, circuit breakers and fuses–what’s known in the industry as over-current protection or OCP–have but one mission in life and that is to protect wires from being overloaded, either in the event of a short circuit or in the event too much current is drawn. (The latter encompasses the familiar “You can’t run the water heater, hair dryer and microwave simultaneously” scenario.) Again, with a few exceptions, they are not designed to protect appliances or equipment; if that gear needs protection, it’s often built in.

The burned shore power connection, which is among the most common causes of boat fires, falls into an entirely different category. As it turns out, the cord end had been previously dropped in the water, retrieved, shaken out and pressed back into service. The connections deteriorated and within a few days the plug was crackling and smoking like bacon on a hot griddle. The dousing in seawater caused corrosion, which increased resistance, which in turn led to heat generation, but not a short circuit or overload. Even if cord ends don’t go for a swim, they can still become a fire hazard by simply being inserted into a twist lock receptacle without the added twist and then engaging the locking ring; partially inserted plugs have been the source of many a shore cord overheating, failures and a few fires.

The dockside shore power source in this scenario, a 50-amp 240-volt service, was capable of delivering 12,000 watts of energy, and it did just that, dumping much of that into the high-resistance connection. The average hair dryer is 1,500 watts, so just imagine how much heat could be generated by 8 times that amount. High-resistance connections typically don’t cause dockside circuit breakers to trip, as the breaker doesn’t “know” whether the energy is going to an electric range or a smoldering connection.

Circuit Breaker & Fuse Etiquette

While the previously described scenario isn’t one a circuit breaker or fuse could have prevented, OCP is capable of protecting the vast majority of wiring aboard a vessel. It’s worth reiterating: The primary role of OCP is to protect the wire in the event of a short circuit or overload. It is for the most part not designed to protect electrical devices and appliances. The size or value of a fuse or circuit breaker must, therefore, be selected based on the ampacity of the wire which, in turn, should be chosen based on the anticipated load and desired voltage drop.

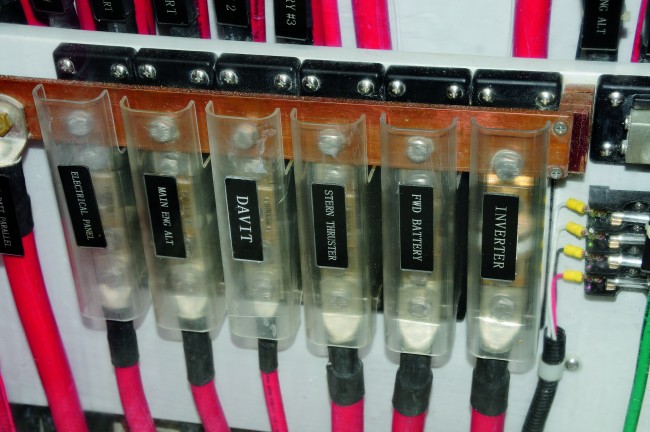

Among the most important regulations governing OCP is the distance rule. While this tends be a DC issue, it applies to AC and DC equally. With a few exceptions (i.e., wires serving starters and wires shorter than 7 inches) every positive DC wire must be equipped with OCP within 7 inches of the battery terminal. If the wire is sheathed with corrugated loom, is inside a conduit or even wrapped with electrical tape, the distance can be extended to 72 inches. For wires connected to battery switches and starter posts, the 7-inch rule remains; however, if sheathed, OCP needs to be installed within 40 inches (rather than 72 inches). For AC wires, the maximum distance a wire can travel before OCP is installed is 40 inches, with a few exceptions, which are detailed in American Boat and Yacht Council Standards Chapter E-11, which covers AC and DC electrical systems. Among the more common violations are battery charger wires connected to batteries, many of which include no OCP whatsoever. For shore power, OCP must be installed within 10 feet of the inlet. Regardless of the distance rule, every foot of wire between the battery or AC electrical source and OCP is unprotected. If a short circuit occurs, the wire will overheat and its insulation, and possibly combustible materials around it, will burn. Thus, the closer OCP is installed to the power source, the better.

Absent or improperly located OCP is the most common electrical defect I encounter in the vessel inspections I conduct. It is, above virtually all other maladies, the one that keeps me up at night, and it should keep you up too. If you are unsure about your vessel’s OCP, call an ABYC-Certified marine electrician and ask him or her to carry out an OCP review of your vessel.